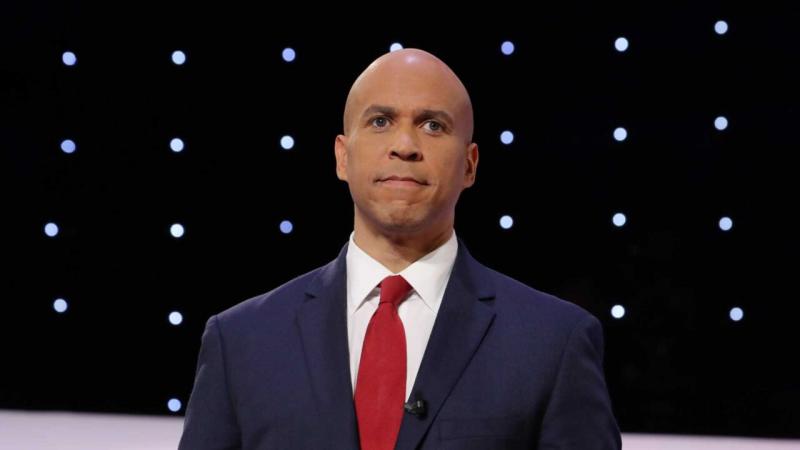

Cory Booker Speech: Let America Be America Again

Watch this famous Cory Booker Speech. Cory Booker went to Google Zeitgeist to explain to us serious problems that the United States has been facing for years and years. He’s an American politician serving as the junior United States Senator from New Jersey since 2013 and a member of the Democratic Party. Enjoy our Speeches with subtitles and keep your English learning journey.

Cory Booker Quote:

“If you want extraordinary results, you must put in extraordinary efforts. ” Cory Booker

Cory Booker full

Download available

for Plus Members

🎯 1000+ English files (PDF, MP3, Lessons)

PDF Transcript

Access the full speech in an

easy-to-read PDF format.

Audio Version

Listen and download clear,

high-quality MP3 recordings.

English Lesson

Includes vocabulary

and grammar practice.

Offer ends in:

01

Days

:

15

Hours

:

29

Mins

:

42

Secs

Offer ended.

TRANSCRIPT:

Download available

for Plus Members

PDF Transcript

Access the full speech in an

easy-to-read PDF format.

Audio Version

Listen and download clear,

high-quality MP3 recordings.

English Lesson

Includes vocabulary

and grammar practice.

Offer ends in:

Offer ended.

“I’m in this weird state in my life where I’m incredibly excited. I literally get up every morning with this amazing enthusiasm about what can be but this very deep sober understanding of what is. I feel this amazing, awesome, sense of vision about where we are — could go as a country, what I desperately believe is our destiny.

But I get very humbled when I look at the challenges. And I want to jump into this in a way that you may not expect. But I would like to take us to what is a reality for thousands and thousands of Americans and a moment of mine when I wasn’t in selected office.

It was 2004. It was April. My father was visiting me for my birthday. And we were taking a walk in my neighborhood. I lived at that point in the central ward of Newark. Newark is a City of great diversity with wealthy neighborhoods, with poor neighborhoods. This was one of the poor census tracts in our city. I was living in some high-rise public housing projects.

We were walking down the road. I will never forget the gunshots that rang out sounded like cannon fire because they echoed between many of the buildings. I turned around to see kids running down the hill towards me screaming. I sprinted through the children to get to the steps where I saw another kid sort of holding onto the bannister, stumbling backwards. And I caught him in my arms. Looked over his shoulder and I saw his white T-shirt filling with red blood. I remember putting him down on the ground, screaming at people to call an ambulance. And blood just seemed to be coming from everywhere.

I found out his name. His name was Juazin. I drew my hands into his bloody shirt, having no medical training whatsoever, just trying to stop the blood. It was like nothing you see on TV. There was no eloquence about it. It was just messy and disgusting. Blood was pouring from his mouth. I stuck my fingers in because I heard him gagging, trying to clear his airway. It was continuous. It seemed like hours until the ambulance finally arrived.

By that time, his body was lifeless. I was pushed out of the way. They ripped open his T-shirt, and he had three bullet holes in the front of his chest and one on his side. I remember getting up off the grass where I was just sitting watching the emergency personnel try to save his life. And he was, unfortunately, by that point dead. And walking over to my dad who looked at me covered in another boy’s blood, and I insisted he went home. I stayed and talked to the police. I went home. I lived on the top floor of these projects. I walked up the steps, 16 flights. Get to the door. My dad opens the door.

We have this moment where we’re just staring at each other. Now, my dad is a guy who says all the time that he is the result of a grand conspiracy of love. And, thus — and, therefore, you are, son, not only born in a — from a grand conspiracy of love; but you were born on third base. And don’t ever think you hit a triple. Your father was born — your father was born to a single mother. Born poor. And, in fact, he’ll get upset with me if he hears me call him born poor. “I was just po’, p-o. I couldn’t afford the other two letters.” And he was born in a viciously segregated town in the mountains in North Carolina.

He was born where his mother couldn’t take care of him. He was raised by his grandmother. 11% of kids in my city, or around that, are raised by their grandparents. His grandmother couldn’t take care of him, and then he was taken in by the community. And it was the community that intervened with him, that conspired to make sure he got on the right track in school when he couldn’t afford go to college and said he was going to put it off to work, they said, “You’ll never go to college.” So he tells me this story about getting envelopes full of dollar bills so that he could pay his first semester’s tuition and get a job at North Carolina Central University, a small historically black college in North Carolina.

And then his life then became a story of interventions. He was able to graduate, got his first job thanks to blacks and whites coming together through the Urban League and helping companies hire blacks for the first time. Interventions. He then moved into the first house that I grew up in because of an organization called the Fair Housing Council. Blacks and whites coming together sent out a white test couple who worked with my parents to break open a town that I grew up in as my father called us when we moved in, he called us the four raisins in the tub of vanilla ice cream. But my dad would sit me at the kitchen table and tell me these stories. And it was a conspiracy of love that got us to where we are.

And so now I’m sitting in this doorway with my dad staring at me with a boy’s blood on myself. And I sort of pushed past him and said, “Dad, I just want to go to the bathroom.” And I walked in and I closed the door on my father, my history, my rock, and I stared at myself in the mirror and began to try to scrape this boy’s blood off my hands. And I am a guy that suffers from a severe case of BO. Don’t worry about it, people moving their chairs back. Bold optimism. At this point, I’m staring in the mirror, my hands are shaking. The blood is off my hands. I keep scrubbing because I just feel the blood on my hands. And I felt myself becoming choked with an anger that just is rare to my being.

And I felt angry at this nation that professes where children sing a chorus to our country every day that we are one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. But there’s such a dramatic between the — how could everybody in this room know who I’m talking about when I say Natalie Holloway or JonBenet Ramsey, but not one person in this room could name a kid that was shot this year in an inner city. And there were thousands. I became frustrated with who we claim to be, but the savage realities of who we are.

I then I walk out and I look at my father, who says to me, “Son, I worry about our nation. What battles we have fought, my generation, the generation before me. How we emboldened this democracy, how we made it more real and made it more true, but now I worry that a boy born to a single mother in a poor neighborhood, in a segregated neighborhood, who couldn’t be raised by his mother, was taken in by others, that was born in those circumstances in 1936 has a better life chance to make it than a child born under the same circumstances in 2006 or 2010.” My father, I felt like he was indicting my generation, this generation of astounding achievement, this generation of incredible advancement and access. And he was standing there, looking at me, his son, who was so shaken, and he, this optimistic man, who believes deeply in this country and this nation, as he calls it, a conspiracy of love, how he could there suddenly be doubtful.

And I left that apartment the next morning, and I walked down the stairs, and I slammed into the presence of a woman named Ms. Virginia Jones. And she is — was the tenant president of those buildings and had been since the day they were built. She was an elderly woman. She was about five foot and a smidgen, but I look up to her. And I didn’t even have to have a conversation with her. I saw the back of her head and my funk just disappeared.

And I suddenly felt this sense of hope and excitement again. And the funk disappeared because I interviewed her a few years earlier for an article I was writing a couple years earlier for an article I was writing for esquire. And I told them I wanted to write about American heroes and I picked a woman nobody heard about. In the course of interviewing her, this fearsome woman who had done so much personally. In fact, on my first day meeting her, I was still a Yale Law student, she brought me into the middle of Martin Luther King Boulevard, and said to me, “You want to help me?”

I was lost, and I said, “Yes, ma’am.” And she said, “Okay. If you want to help me, look around you. What do you see?” And I described a crack house, graffiti, all the problems. Then she just looked at me and said, “You can never help me.” And I said, “What are you talking about?” And she looked at me hard, and she said, “Boy, you need to understand something, that the world you see outside of you is a reflection of what you have inside of you, and if you’re one of those people who only sees problems and darkness and despair, that’s all there’s ever going to be. But if you’re one of those people who stubbornly, every time you open your eyes, you see hope, you see opportunity, you see possibilities, you see love, you see the face of God, then you can probably help me.”

And I remember, she walked away on that first moment of meeting her, I looked at my shoes, I said, okay, grass hop per, thus endeth the lesson. So, when I walked out from that building, there’s a story that I remember was her telling me about her son who fought for the U.S. military, who came back to this country and was visiting his mother, his mother got a knock on the door, Ms. Jones did, the woman couldn’t speak, she was crying,

she got grabbed by the woman, dragged down five flights of stairs, and there was her son, shot to death in the lobby, bleeding it red. She told me she fell to her knees and wailed into the echoes of the lobby. I looked at her when she finished that story, and I said, Ms. Jones, I know where you work. She worked for the prosecutor’s — she and I paid market rent to live in these — these buildings. And I said, “I just — I don’t understand. Why do you still live here where you have to walk through the lobby of the building where your child was murdered?” And she looked at me almost like she was insulted by the question.

She said, “Why do I still live here?” “Yes.” “Why am I still in apartment 5A?” “Yes, Ms. Jones, why.” And she goes, “Why am I still the tenant president from the day these buildings were built 40 years ago?” And I said, “Yes, Ms. Jones, why.” And she stuffed out her chest and she said, “Because I’m in charge of homeland security.”

To me, this is what keeps my fired up in Newark, is that I live in a city with the most stubbornly hopeful, the most audaciously determined individuals who have not given up on the truth of the American dream and confront in every moment the unfulfilled, unfinished dream. And there are people that realize in an intellectual and spiritual way that if we who are on the front lines of this fight for America can’t solve this problem, the country as a whole will suffer. As Langston Hughes said, “There is a dream in this land with its back against the wall. To save the dream for one, we must save it for all.” And what gives me hope is, after five years in a job which people told me would grind down my idealism, which would squeeze out my optimism, my hope, which would make an idealist a realist, I’m telling you that I am hope unhinged.

Because I see the national problems that we have every day when I leave my apartment in Newark, New Jersey. And I see how they are cancer on the soul of this country and our economy. But I also see Newark, New Jersey, like so many other cities, are littered with examples, are littered with models that demonstrate to us that there is a way out, and, in fact, that our challenges do not reflect a lack of capacity to deal with them. They reflect a lack of collective will. And this is what has me both so fired up and angry, but also incredibly hopeful and full of love.

Let me deal with two complex problems. And I love talking about these problems to people of any political persuasion, because whether you are somebody who hates big government or believes in government, you have to join with me in saying that perhaps some of the greatest waste in America right now is the fact that we’re investing in systems that produce such abhorrent failure. The criminal justice system is one of those systems that we spend billions of dollars, billions of dollars annually, in a correctional system in New Jersey, for example, that does nothing to correct the problems.

The other system is this system of public education that right now is failing to prepare the majority of our children for a 21st century economy that is a knowledge-based economy. The more you learn, the more you earn. And forget about earn, the more you contribute, the more you grow. Now, the criminal justice system, actually, my team said, this is crazy. My friend, Michael Bloomberg, says this all the time.

We’re unconscious to the fact that every day, we are a Virginia Tech in America. Every single day, there’s 30 plus people murdered in our city, countless more that are shot, every day. And I always joke with my friends, I said, you know, guys who get shot don’t show up to the hospital with health insurance. In fact, we found out the victims of shootings in our city, about 83 or 84% of them have been arrested before. And the average arrests are ten times that they have been engaged in the criminal justice system as adults, not to mention their child arrests. We couldn’t believe it when we started seeing this pattern that we have in America of criminality that becomes ingrained. In fact, generationally ingrained, because the children who most likely go to prison in America are children of incarcerated adults.

And so we started looking at this system and saying, why are we engaged in this ridiculous game that we believe that somehow there’s some correlation between the more arrests we do and the lower crime. There’s no correlation whatsoever. And my police officers, one of them was here, sitting over there on the side — yes, he has his gun with him.

Jim Stier, behave yourself, or we’re coming after you. My police officers could drive by corners and name the guys there. And when we would get out in the corners and I would engage the fellows, the fellows would know who the police officers are. And so we started saying that there has to be the ability for Americans to innovate a way out of this. There’s got to be a way to create radical shifts in realities.

We said, let’s start experimenting with system change to demonstrate in a policy way that we have choices in America to make. And so we started looking around. Who is doing something to end this nightmare that when a person is arrested, that they won’t leave a system with 60-plus, 60 to 70-plus come right back? So we started trying to find new ways. We looked at programs all around the country. First of all, we found out when we interviewed guys that they come out and they all express a desire to do the right thing.

One of my friends who’s very involved in the criminal justice system, guys on the street, says, 5% are knuckleheads. You can go to any profession, from politicians, to you name it, 5% of us are knuckleheads and belong under a prison. But 95% actually are far more rational economic actors than you think. So a guy coming out of prison who can’t get a driver’s license, they know who they are to arrest him, but he comes out, doesn’t have identification, it’s an amazing struggle, doesn’t want to go see the mother of their children because they owe them so much money in child support payments.

Has warrants out for their arrest because in prison they had a traffic ticket, became a failure to pay, failure to appear, with a warrant. All of these administrative law problems, we start listening to them and said, okay, let’s innovate. We found out there was no legal support for these guys. So we pulled all our law firms in Newark together to create the nation’s first pro bono legal service project. And we said to the law firms, help us stop crime. A little bit of administrative law help can help these guys. It was amazing. The law firms found that their associates were loving it, because the liberated the economic potential of guys, helping them expunge records, get driver’s licenses and IDs. We said, look at these guys, they’re coming out and they need rapid attachment to work. This is a bad economy.

But let’s find out ways to get them attached to work. We’ve done everything in Newark from partnering with businesses to start a niche in our city. We didn’t have any fumigation businesses based in Newark. We started solely for the purpose of hiring guys when they come home. It’s called Pest at Rest. I did not think of the name.

We realize guys, there’s got to be a better marketer in this room, please. It sounds like a spa for bugs. We found out that guys coming home, that one of the biggest things they said they wanted to be, imagine this, was great fathers. But yet they were often absentee fathers. And you talk to them about why that was, and there were logical reasons that they had for not being involved in their kids’ lives. So we created a partnership program with these guys where we brought in other men to be mentors to the guys, fathers being mentors to other fathers. We actually created a fraternity of men around it. It wasn’t in a fraternity at Stanford, but I wanted to create one, so we created Delta Alpha Delta Sigma, DADS.

And we had parenting classes. I learned how to be a dad even though my parents are saying, why aren’t you one. I learned how, because at 5:00 in the morning, when I was in first grade, the first sound I would hear on a snow day was my dad shoveling snow, because he was going to get to work. We started having group activities for the women, and helped the men negotiated child support payments, took care of everything, and before you knew it, we had this program that now over five years has a recidivism rate not where New Jersey’s is, about 65%. It has a recidivism rate lower than 3%. We have a program now, a one-stop center, partially funded by the Manhattan Institute.

I got a right-leaning think tank in New York, partnering with grass-roots activists who can’t say the word Republican without gagging, but partnering in Newark city hall with a program right now that for the men that come to our — men and women who come to our program, we have a 70% placement rate for jobs, working with local companies. That one small aspect of our program has saved the state of New Jersey millions of dollars. We are Americans. There is nothing we can’t do. But we allow ourselves to get caught in the grooves of a record playing the same old tired song over and over again, surrendering our power, surrendering our authority, surrendering our responsibility.

In fact, we get into a state of what I call sedentary agitation, where we see the kids shot on TV and inner city. We’re upset about it, but we take no responsibility for it. We don’t get up and do something about it. We fail to say that our destiny is fully linked up with the destiny of another American. And I know it is. Go to Google and put in the words, “McKinsey disparity education.” A report will pop up, a 2009 McKinsey report, where they looked at the impact in America of the disparities of educational outcomes alone. They said the impact on GDP alone is about 1.3 to 2.3 trillion dollars, trillion dollars.

You see, something I know is that genius is equally distributed in America, equally distributed. You’ll find it everywhere from inner cities to suburbs, from farm areas, and that our greatest natural resource as a nation is the minds of our children. But yet we’ve rolled them away in more of a gross offense than the oil spill in the Gulf. And the reason why I get excited about this problem is because we’ve shown ways of solving it. I could take you to Newark, New Jersey, right now, and show you schools in my city that are outperforming the wealthiest suburbs.

The answers are there. The question is, do we have the will? I talked to the Ford Foundation and they’re, like, we’ve spent lots of money in investment, but we know some of the things that actually work. We’re doing them in Newark now. Some of our schools just take simple equations. Like, when I was going to school, time was a constant, achievement was the variable. You go to school 180 days in New Jersey. If there’s a snow day, they’re going to smack another one on. Even if we were, like I was, in Harrington Park Elementary, sitting in the cafeteria watching reruns of The Little Rascals.

You’re going to be in that building 180 days. Look at contracts for teachers and principals, it’s all about time. My highest-performing schools in Newark have switched that equation around and said that achievement is going to be the constant; time is going to be the variable. They go to school, longer school days, longer school weeks. We have Saturday classes, mandatory Saturday classes. Longer school years. And funny enough, that’s what our competitor nations are doing.

The answers are out there. Whether in reforming our criminal justice system, I can tell you from all over our country, incredible things in innovations are going on. In education, we see things that are working but we are lacking the political will, the collective will, the individual will. I’m a mayor of a big city. I have got a lot of things to do. But I see it all the time. If every American who was able just mentored a kid — You can actually do online mentoring now. All mentoring, I have seen study after study shows you drive down the level of criminal activity. You drive down the level of early sex practices.

You drive up the success of schools. But, yet, we as Americans, who drink deeply from wells of freedom and liberty that we did not dig, we lavishly eat from banquet tables that were prepared for us by our ancestors. We are too often just sitting around getting drunk on the sacrifice and struggle of other people’s labors and forgetting that we are a part of a noble mission in humanity, the first nation formed not as a monarchy, not as a theocracy but as an experiment, an idea that a diverse group of people, that when we come together, e pluribus unum, that we can make a greater whole out of the sum of our parts. So here we are, standing at a crossroads in our country.

We are cannibalizing ourselves by segregating our populations: Poor and not poor; educational access and lack thereof; high-crime areas, spending more and more money; and finding ways to liberate people from these dead-ends of life, from the carnage of human potential. And to me it is a choice, just like every moment of our life is. We either choose to accept conditions as they are or take responsibility for changing them. Well, I know what our history is. I know what the calling of our ancestors is. And so I will end, and I’m looking forward to our panel with a poem that I’ve begun to say more and more, that my parents would read to me as a child, as they would tell me the stories of how lucky I was to be born where I was, how lucky I was to have the opportunities I have, how the experience I was having as a young Black man in America was a dangerous dream to my grandparents when they were growing up.

My parents read me this poem from Langston Hughes: O let America be America again. The land that never has been yet but yet must be the land where everyone is free, the poor man, the Indian, the Negro, me. Who made America? Whose sweat and blood, whose faith and pain, whose hand at the foundry, whose plow in the rain must make our mighty dream live again? Oh, yes, I say it plain. America never was America to me. But I swear this oath, America will be.

Our generation must say collectively not on our watch. This will not be the generation with more people in poverty than our parents. This will not be the generation with lower literacy rates than our parents. This will not be the generation where our economy declines in comparison to the rest of the world. We know we have the capacity. But as our leaders have said, there can be no progress without struggle. As king said, change will not roll in on the wheels of inevitability. It must be carried in by patriots and soldiers for truth and justice and, I say, the American way. Thank you.”[/read]

Cory Booker Speech

Follow us on social media: